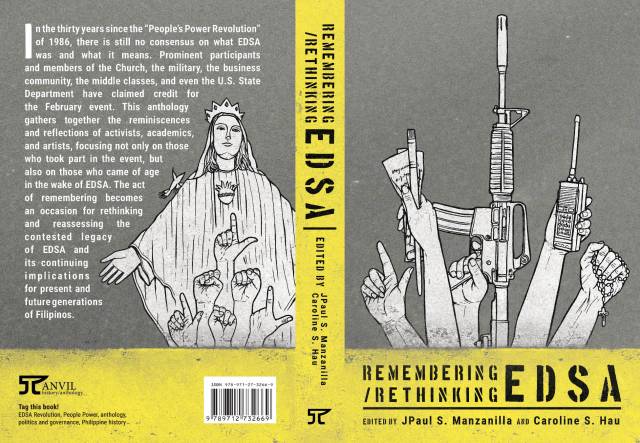

This comes too late for the Afterword I’ve written to the volume Remembering EDSA/Rethinking EDSA (co-edited with my friend JPaul Manzanilla), which has just been published by Anvil, so I am making the factual correction here.

In the Afterword, I tried to trace the origins of the term “crony capitalism”, which was first applied to the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos and the style of plunder he, his family, and his cronies engaged in, plunder that kept a few cronies rich while the majority of Filipinos lived in poverty.

Former Representative Felicito C. Payumo had claimed that it was Jaime Ongpin who coined the term “crony capitalism.” The word “crony”–which has old roots in American politics–was popularized in Marcos-era Philippines by Ricardo Manapat, whose 1979 exposé, “Some are Smarter than Others” (later published in 1991) listed the financial dealings of Marcos’ close friends and associates, the so-called “Octopus Gang,” among them Roberto Benedicto, Rodolfo Cuenca, Eduardo Cojuangco, Lucio Tan, and Ricardo Silverio, whom Marcos placed in key positions in charge of quasi-state monopolies and other big enterprises in cash-crop (sugar, coconuts, tobacco), manufacturing, financial services and construction sectors. While Jaime Ongpin, whose brother Robert had been a Marcos technocrat, is generally credited with calling international attention, in his June 1981 letter to Wall Street Journal, to the “avarice and incompetence” and “gross exploitation of political connections and unbridled access to government financial institutions” that he deemed responsible for deepening the economic crisis that hit the Philippines in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was not Ongpin who coined the term.

The credit for coining the term actually goes to Time business editor George M. Taber, who first used it in an article by John DeMott on the Philippines that Taber edited in the April 21, 1980 issue of Time called “The Age of Crony Capitalism.” Taber attributed the poor performance of the Philippine economy then to the “Philippine distortion of the capitalist system,” a “weird distortion of the free market” where “the cronies got richer and the poor stayed poor.”

The immediate context for the sluggish Philippine economy was the U.S. Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates in 1979 and falling commodity prices, which had saddled the Philippine state monopolies and semimonopolies with debt. Marcos’ decision to bail out these companies was heavily criticized by the Philippine and international business community as an act of favoritism that benefited only the cronies and relatives.

In more recent times, crony capitalism has sailed beyond Philippine shores and migrated to a host of other countries. “Crony capitalism” acquired regional currency during the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis, when American officials such as William Clinton, Robert Rubin (whose career in fact is a nice illustration of crony capitalism in action) and, most especially, Lawrence Summers employed the Philippine-coined terms “cronyism” and “crony capitalism” to lay the blame for the Asian crisis on the cozy collusion between government and business, particularly in Southeast Asia. In its Crony Capitalism Index (2014), the Economist ranked Hong Kong (1), Malaysia (3), and Singapore (5)—the three countries that experienced the East Asia Miracle—above the Philippines (6) in the list of countries where “politically connected businessmen are most likely to prosper.”

The term has come back to haunt the Americans, who are now wont to apply it to their own country and talk about how crony capitalism is alive and well there, along with their own oligarchy and deepseated inequality. When the Lehman Shock occurred, the American government let the insolvent Lehman Brothers go bankrupt, while bailing out AIG and Bear Stearns. Now it is the Americans who are making the case for “crony capitalism.”

Marcos certainly did not invent crony capitalism, but it was the Philippines under his helm that became the typecase for that phenomenon. Crony capitalism is, along with People’s Power (and “edifice complex”, first used by Rafael Salas to describe Imelda Marcos’s building mania), one of the terms that sprang from the study of the Philippines and is now part of academic and popular discourse.

Remembering EDSA/Rethinking EDSA

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments, ix

Introduction

A Season for Remembering: People’s Power, Democratization, and the Memories of a Revolution by JPaul S. Manzanilla, 1

The Revolution across Generations

People Power: Deception and Truth in a History-Changing Event by Filomeno V. Aguilar, Jr., 42

EDSA and Its Aftermath: Lessons in the Production of Meaning by Alice G. Guillermo, 73

The Marcos Memes and the Manipulation of Memory by Jose Santos P. Ardivilla, 84

A View of the Fall of Marcos from Inside and Outside Prison by Jose Maria Sison, 106

“People Power” 1986 in Retrospect: A Conjunctural Analysis by Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, 122

Naging Mabunga Sana ang EDSA 1986 para sa Kilusang Rebolusyonaryo ni Lualhati Milan Abreu, 137

EDSA Viewed and Lived from the Left Field: Struggling Forward in Confusing Times by Dominique Caouette, 154

Grains and Flickers by Joel David, 172

Pag-aakda: Paglulugar ng Sarili sa mga Kuwento ng Aking Bayan ni Eulalio R. Guieb III, 188

Desperately Seeking Bernardo Carpio by Luis H. Francia, 198

Stalking EDSA by Angela Stuart-Santiago, 211

Computers, Political Prisoners and Punk Music by Bomen Guillermo, 227

Owning EDSA by Katrina Stuart Santiago, 233

Refragmenting EDSA: Supplications and Insults for the Nationalist Baby Boomer by Lisandro E. Claudio, 244

Mob by Michael D. Pante, 249

Creative Critiques

Being the Recollections of Private Faustino Sabado of the 5th Battalion Marine Landing Team on What Transpired between February 23 and 25 1986, as Told in Bisayan to and Roughly Translated into English by Patricio N. Abinales, 256

EDSA Mob ni Mark Angeles, 272

May Puting Rosas ni Maricristh T. Magaling, 274

Villanelle sa Pagbabago ni Soliman Agulto Santos, 275

Mga Sandali ng Tubig ni Mark Benedict F. Lim, 276

Parable of the People by Gémino H. Abad, 291

Poem 12 from “Troubadour” by Edel E. Garcellano, 294

GMA Resign Comics ni Kendrick Bautista, 296

Selected Artwork by Jose Tence Ruiz, 297

Curfew ni Carlos Piocos III, 307

Class and Ideology, Technocracy and Technology, Culture and Revolution

The EDSAs: From Cross-class to Class-based by Mark R. Thompson, 310

Philippine Technocracy and the Politics of Resiliency and Retribution by Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, 325

The Cell Phone and the Crowd: Messianic Politics in the EDSA II Uprising by Vicente L. Rafael, 339

A Cinema in Transition: Initial Incursions by Patrick D. Flores, 359

EDSA in Context: An Uprising 14 Years in the Making by Luis V. Teodoro, 377

29 sa Anino ng Mamasapano ni Teo S. Marasigan, 381

Recalling History, Revoking Democracy by Neferti Xina M. Tadiar, 392

Afterword

People’s Power, Crony Capitalism, and the (Anti-) Developmental State by Caroline S. Hau, 398

About the Authors, 449